By: Vida Manalang & Jeff M. Poulin

Fostering meaningful youth-adult partnerships is an essential part of supporting youth agency in arts, cultural, and creative learning environments and beyond. Young people are capable community contributors with the right to participate in the creation of projects and programs that affect their lives directly.

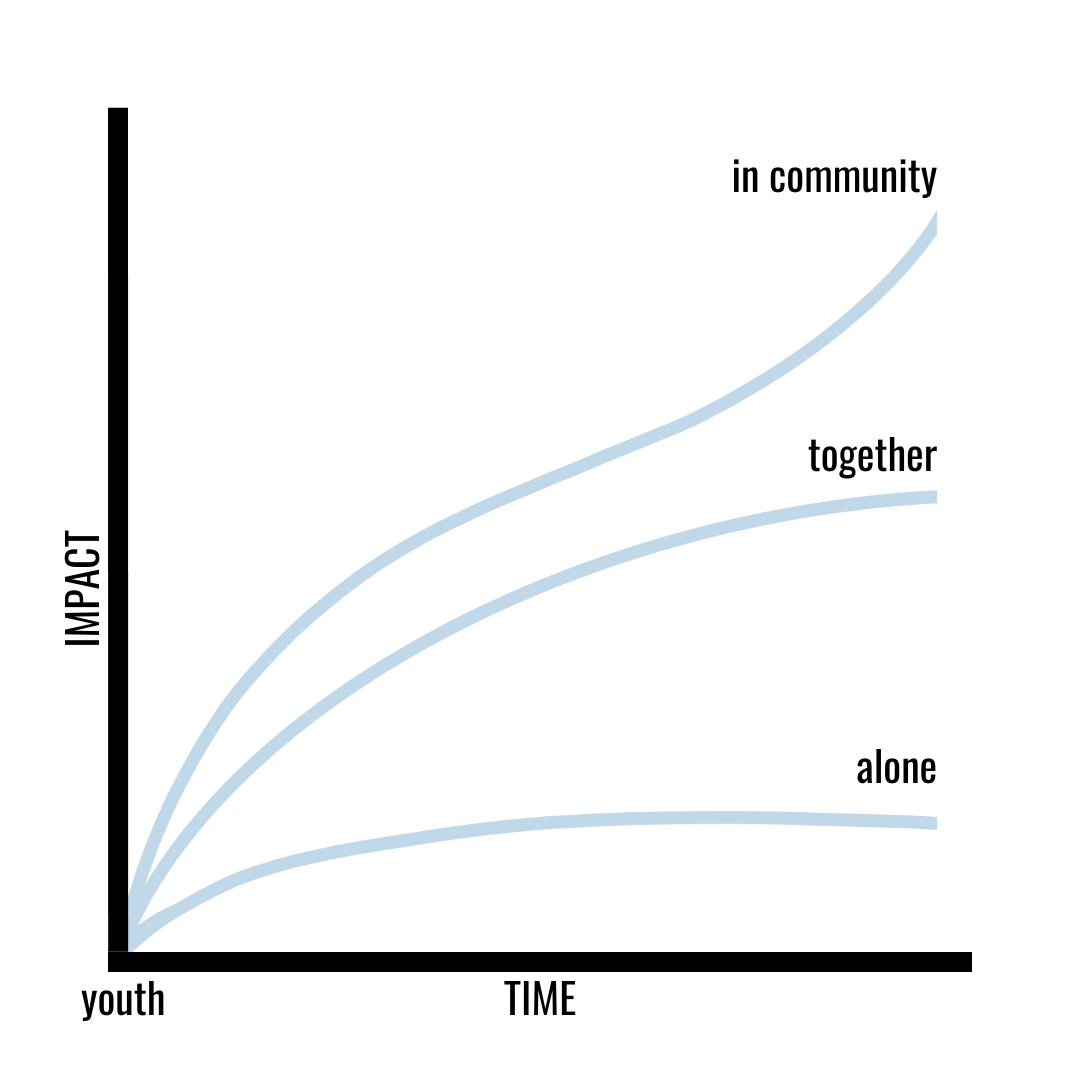

In our work commissioned by ArtPlace America, Creative Generation collaborated with a team of youth-adult pairs to research and document the impact of their youth-led, community-based creative projects. It was profoundly noted through the perspectives of young creatives engaged in this project that the impact of creative projects is exponentially greater when we work together, intergenerationally, “in community.” When defining this term, “in community,” the young creatives explained that it does not mean ‘working within the community’ (like neighborhood or amongst groups of people), but rather ‘working in community’ (as collaborators).

This impact was diagramed and explained through movement and music by the youth researchers and is represented by the quote and graph below:

This approach harkens back to some early work of Creative Generation, specifically Jeff M. Poulin and Jordan Campbell, on the concept of cyclical mentorship.

Cyclical Mentorship

Cyclical mentorship is an assets-based approach to mentorship, where focus is placed on individual strengths and the diversity in thought, culture, and traits. This work emerged from a 2017 dialogue and subsequent initiative, and was later expanded through a series of projects and writing, found below:

Unlearning Ageism: Expanding The Definition Of Mentorship In Arts & Cultural Education

MODERN MENTORSHIP: The Solution That Has No Name: Revisiting Cyclical Mentorship

To sum up the core of this inquiry, we often refer to an early session exploring this topic when one attendee pondered, "So, it's like redefining who is the 'question-asker' and who is the 'answer-giver'?" Emphatically, yes!

In this model, we see the dynamic relationship between young people and their adult educators, as well as intergenerational relationships between emerging, mid-career, and veteran practitioners.

A key element to employing the concept of cyclical mentorship is the empowerment, cultivation, and honoring of youth voice.

Equitable Intergenerational Collaborations

Youth voice is used to describe the collective ideas of young people. It is a matter of citizenship and participation in a democratic society, according to sociologist, Roger Hart. Consulting youth voices and placing youth at the heart of partnerships of any kind allows for youth cultural and creative lived experiences to inform initiatives going forward. Youth are able to design and manage complex projects if they have ownership in the work being done. The more youth are involved in the development process, the more likely they will feel motivated to participate and foster their own skills and competence in democratic participation. Partnership and shared leadership between youth and adults benefits all stakeholders of a project as it widens the perspective of an organization and inspires innovative solutions to challenges that affect now and future generations.

Roger Hart, in his field-changing publication from 1992, applied the framework of Sherry Arnstein’s Ladder of Citizen Participation (from 1969!) to visualize the concept of youth participation. Hart’s Ladder of Children’s Participation has eight rungs that represent the continuum of youth power ascending in agency from non-participation (no agency) to degrees of participation (increasing levels of agency). Though several variations and models expanding upon Hart’s Ladder exist, their foundations lie in the ascension of youth non-participation to shared leadership with adults.

Hart’s originally proposed Ladder is known for its simplicity and clarity in organizing types and degrees of youth participation. The existence of this shared language was an asset to the developing Creative Youth Development field. However, in 2008 Hart was critical of his own model, as it was not intended to be used as a comprehensive evaluation tool for program participation. Hart notes shortcomings and assumptions that have emerged in the application of the Ladder to program development.

The most important piece of critique on the original model in context to the graphic below, is that the Ladder image automatically creates assumptions about sequential stages of development - with the top rung representing an ideal model of participation. This was not Hart’s intention. He further clarifies that there is no stepwise motion in developing participation and that there is no youth participation that is inherently ‘higher’ than another. All versions of participation are necessary in the initiation of conversations with young people towards creating a project or program. Hart encourages the creation of new, evolving, and culturally contextualized models for use in evaluating youth participation. So, it seems necessary to reimagine this framework as a more useful, values-neutral tool for arts, cultural, and creative educators seeking to foster equitable intergenerational collaborations.

Cultivating the Conditions for Equitable Intergenerational Collaborations

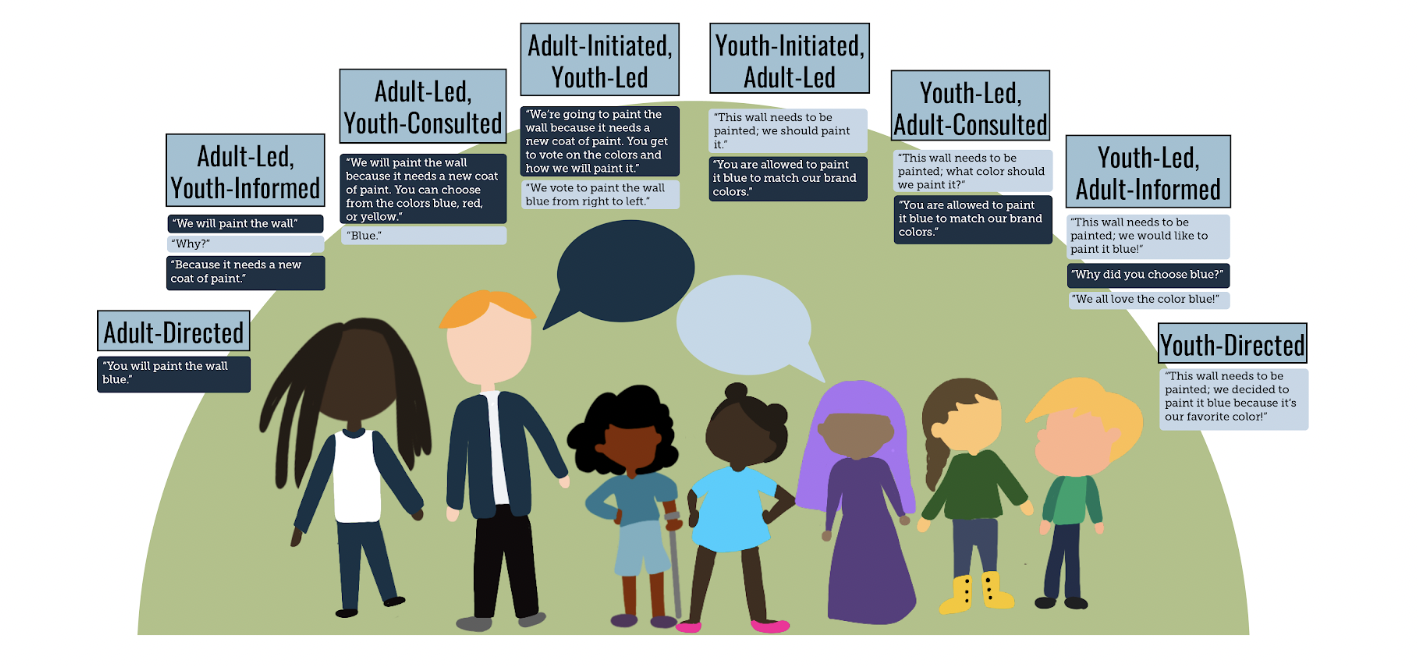

At Creative Generation - through a collaboration with Boys & Girls Clubs of America - we have spent time uncovering the possibilities of a spectrum (versus a ladder) of youth-adult partnerships relevant to arts and cultural education programs.

In the below diagram, one can identify and place themselves in the relevant category; you might read this like a speedometer. Much like driving, before you, as an educator, can determine the speed of your car and apply the gas, you must consider the conditions, like the terrain, curvature of the road, and visibility. The same goes for working with youth: before determining the type of intergenerational collaboration, we must inquire about the conditions and apply collaboration equitable to meet the needs of the youth collaborator.

The categorization below is intended to provide vocabulary and some "rules of the road," if you will, about how to navigate the power-sharing. It is not a judgment on the efficacy of the partnership; there is no right-or-wrong about the level of youth voice or leadership in any project based on the category.

From left to right, Adult-Directed participation refers to a project - in this case the painting of a wall - being proposed by an adult without consulting youth and the directing of youth to carry out the task without question. In this case, youth are often not informed that they may have a say in what is being asked of them. This model is present in traditional classrooms and learning environments where an educator is explicitly providing information or instructions on how to complete a task or lesson.

In the scenario of Adult-Led, Youth-Informed participation, youth are able to question why a certain activity or project is being presented to them. They have a voice in this situation and are allowed to speak up, but are not in positions to enact actual change of action. In our example, youth are able to ask “why” and are provided an answer but cannot interact with the decision being made.

In Adult-Led, Youth-Consulted participation, children are informed of why a task or initiative is and are asked for input based on a framework given to them by adults. Youth are asked to contribute within existing parameters of choice. In this example, youth are presented with a choice of colors to paint the wall. The choices were predetermined by an adult, but youth did have a say in what the outcome would be.

In Adult-Initiated, Youth-Led participation, youth propose an idea or solution to their own needs without influence or instruction of adults. Adults set expectations for and collaborate with youth on how best to align with and achieve youth vision. In this example, youth notice the need to paint the wall and definitively propose a solution - to paint it. Adults respond by giving youth permission to paint the wall and reasoning for what color to paint the wall to serve both their visions.

In Youth-Led, Adult-Consulted participation, youth propose an idea and a solution for their idea. Youth identify the need to paint the wall, and want to paint the wall. Youth work with adults as collaborators, actively consulting adults about what color the wall should be painted. Adults provide permission to paint the wall, and reasoning for what color to best paint the wall.

In Youth-Led, Adult-Informed participation, youth propose the idea to both paint the wall and have already decided the best color to paint it based on their own opinions and needs - without the influence of adults. Youth inform adults of their decision and adults are able to have a conversation regarding their reasons for choosing the color blue, but do not seek to change or impose their own beliefs or needs onto youth. Youth are able to freely express their reasoning and engage in conversations with adults about their task. Adults are responsible for remaining informed and updated during the project or activity.

In Youth-Directed participation, youth see a need and propose a solution for this need. In this case, youth see that the wall needs paint and they decide to serve this need by painting the wall. Youth also decide what color is the best for this project, this is not influenced by adults or larger organizational needs. The decision on color is made based on their own preference and of their own agency. This participation is completely initiated and led by youth.

As you employ this tool, it is important to note who initiates the conversation and how much of the “why” is in the youth or adult’s control.

A Consideration for Sustainability

Finally, as one determines the sustainability of our equitable intergenerational collaboration, it is encouraged to think about succession plans. Vida Manalang, conducted a study examining organizational leaderships in transition and the elements of succession planning, particularly between founders and alumni successors. Here is the model derived from the set of international paired interviews.

Both youth-led programming and succession planning should be elements of an arts & cultural education leaders's job; so too, should be the cultivation of the conditions for that transition to thrive - these include:

Joy,

Creative Thinking,

Trust,

Transparency,

Process-orientation, and

Community.

You can imagine how they may interact in your organization and circumstance around leadership (and for everyone this will be different). What was noted in this study was how this integrated, complex process can look in the eyes of those involved. A values-centered approach, with these elements at the fore, led to sustainable transitions.

-

Manalang, V., Poulin, J. M. (2023, April 13). Practicing Equitable Intergenerational Collaboration. Creative Generation Blog. Creative Generation. Retrieved from https://www.creative-generation.org/blogs/practicing-equitable-intergenerational-collaboration